Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about how to work through an idea. I’ve worked hard over the past couple of years to try to reign in my perfectionist tendencies that often result in procrastination. (Remember when I didn’t hang pictures in our house for six years?) I used to think it was mainly a problem of “creative types,” but, after a little more consideration, I think it’s just a people problem.

I could devote an entire post to where ideas come from, but today my real question is what to do with them once they’re here. How do you work through an idea? How do you know when an idea is ready to execute? And how do you know when the execution is the best it can be?

One thing that spurred these ideas about ideas (is that what the kids call “meta”?) was Alex Blumberg’s recent appearance on The Tim Ferriss Show. He was talking about working with Ira Glass, the host and producer of This American Life, who is a perfectionist known for his editorial gift. “Editorial” meaning he’s a great “editor”–when he works with his team, he often can figure out how to take an idea and mold it into the right outcome. Here’s what Alex had to say about Ira:

What I learned is that a lot of it is just about the effort you put in… But watching Ira work–a lot of times he just keeps thinking about it longer than other people keep thinking about it, and then, eventually he comes up with an idea that’s good. And it just made me realize that that’s how people get to good ideas is they go through a lot of bad ideas first… So what being a perfectionist is is putting in a little bit more time to think through the level 1 ideas or the level 2 ideas to something that’s a little bit deeper.

Pablo Picasso agreed. (This statement is from a series of interviews collected in Brassai’s Conversations with Picasso. I read it on Brain Pickings.)

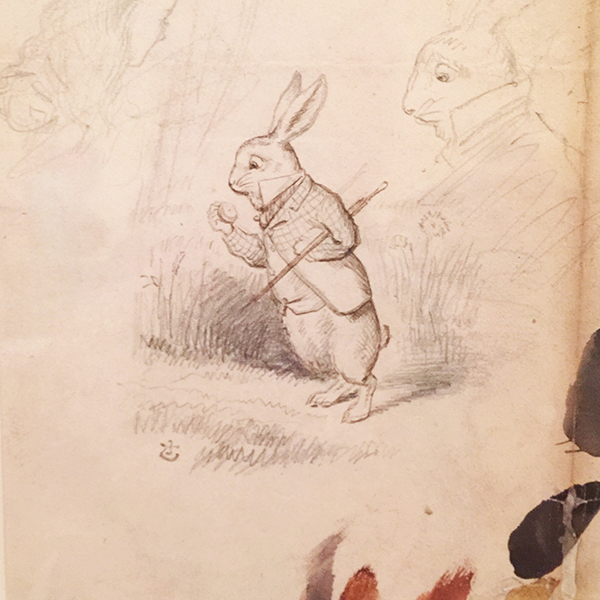

I don’t have a clue. Ideas are simply starting points. I can rarely set them down as they come to mind. As soon as I start to work, others well up in my pen. To know what you’re going to draw, you have to begin drawing… When I find myself facing a blank page, that’s always going through my head. What I capture in spite of myself interests me more than my own ideas.

So you have to be willing to put in the time. But how do you work through the initial ideas to get to the better ones? Here are a few methods to try:

Rinse & Repeat. Henri Matisse was a great lover of repetition. (Also, read that here.) By drawing things over and over, he believed he could distill his subject down to it’s essence. When you do something repeatedly, what once seemed difficult, soon seems like second nature. When the original action is second nature, it’s easy to concentrate on other details, which often lead to even better ideas.

Talk to other people. I often find myself repeating the mantra, “You can’t create in a vacuum.” One great way to work through an idea is to bring it up to people that are different (read: smarter) from yourself and get their thoughts. Maybe they have a relatable experience or can look at something from a different viewpoint that is helpful.

Make lists. Sometimes lists help us think around any relating factors to flesh out an idea. For instance, if you’re planning a dinner party, it’s easy to brainstorm how you want your Southern-Living-worthy soiree to go down. But if you’re trying to really think through the idea, try to make a list of all the things that could go wrong. Fleshing out an idea means looking at it from every angle.

How do you know when an idea is the best it can be? Well, in my experience it’s usually a mixture of intuition and letting things go. When an idea is stretched as far and iterated on as much as you possibly can: let it be. This idea will inform the next idea that will, in turn, inform the next. Be thankful for what you have made, and then move on to greener pastures!

What about you?

Any sure-fire way to think through your ideas?

I’d love to read about them in the comments.